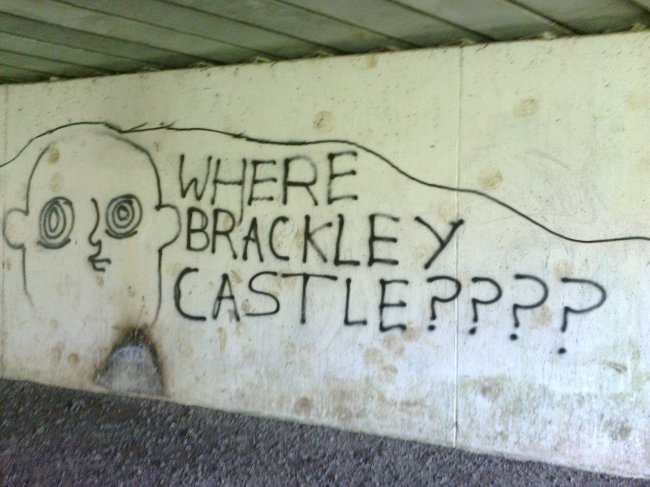

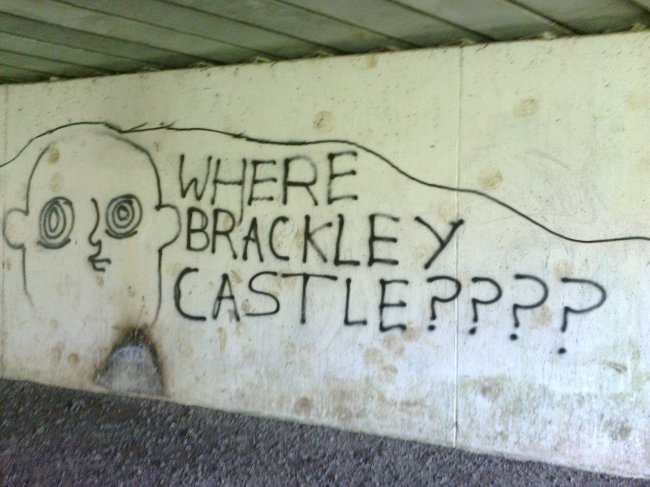

An opening salvo on my walk from Brackley, Northants, emblazoned on the underpass of the dual-carriageway bypass. It’s an interesting question, though not one I pay much head to. At least, not yet. I am heading on out on a kind of (partial) circumambulatory of the town, exploring the old footpaths, disused roads and abandoned railway lines that are so often found dotted around the countryside of Britain.

I had been living in Aberdeen for 18 months; Scotland in general for some 9 years, but soon I will be living in Bristol. Bristol is in stark contrast to Aberdeen. Aberdeen suffers from icy-cold arctic winds racing in from the east, and a seemingly permanent grey ceiling of dreich sky. The buildings are of grey granite (though touristic interpretations label Aberdeen the ‘Silver City’), and the predominant industry is of that the black-grey fossil-slime of crude oil. Bristol, on the other hand suffers far less from such melancholy associations, with its cream-coloured churches and a more temperate climate. It is also due to be the European Green Capital in 2015; a label I think Aberdeen would struggle to attract (“you’re cycling to work?” asked a colleague in Aberdeen; “We have another organ donor!”).

But enough of the (perceived or real) differences between the two cities. I am staying in Brackley, as this is where my parents bide. There’s a lag between tenancies, so this will act as a stop-gap. In a sense, this town is far closer to Bristol (two hours) than Aberdeen (eight or more), but in a strange way, it is the perfect mid-way point. I did a lot of my growing up just a few miles from Brackley in a tiny village called Lillingstone Lovell. A pretty place, with no public transport, and (at the time) a post office, that sold only stamps. But my mother had been told that this village is the second most inland place in the UK. I have quizzed her about this since, but she doesn’t remember where she heard this, or which place holds the number one spot. I like that the stop-gap is so landlocked: and this is why it feels sort of halfway between. Both Aberdeen and Bristol are saline cities, of tidal patterns and waves, salt air and harbours. Conversely, Brackley has just a small unnavigable river. Indeed, Northamptonshire is said to have no brooks running into the county, only ones flowing out, such is its elevated position.

I need this walk. I lived and went to school for part of my adolescence in Brackley, but coming back, the humdrum, everydayness has vanished: where once it was a place to endure, now it becomes a treasure; something jewel-like, with the golden sandstone townhouses and rolling fields of yellow rape and pastel-green wheat.

I have a loose plan: head for Evenley and its pub on the green, then back to Brackley. Despite its proximity to Brackley, I only recall visiting twice – once for a rave in a barn house (free, but legal, if you’re wondering), and the other for the pub.

* * *

The underpass is behind me, and so too is the River Great Ouse, but soon I reach a flooded section of tarmac path; its elevation too low for the standing water to make it to the river. Clambering through the undergrowth, my unsuitable footwear is soaked through: “I hope this warm weather dries my feet”. A field next, rising up to the old Buckingham Road, abandoned and gated (though I recall a gypsy encampment once sited here). Soon, a bridleway: green and yellow fields; trees in varying states of undress – this is early spring, and not all the trees have reacted. I wonder if some are ash: perhaps they will never come into leaf?

Now, a low point in the track, and the remains of a railway bridge. Brackley once had two railway stations: one demolished (though The New Locomotive pub is a reminder); the other a tyre and exhaust centre.

Railways and Brackley are a controversial topic: the High Speed rail line looks set to pass nearby in a vast cutting. But I wonder: is the opposition universal? There’s more graffiti in the underpass; a poem called ‘The Signalman’s Lament‘, written by Mr. L. Wills, bemoaning Mr Beeching’s death of the line:

There might be widespread opposition to the new line, but this is the most visual message I see on my walk that makes reference to railways. Does this tagger embrace the new prospect? Or is it a coded reference opposing the new line, being as there will be no new station anywhere close by? Also: is the artist responsible someone I once knew?

* * *

I carry on through rolling fields and left-over copses. A family geotagging (“we’ve gone the wrong way”; “you mean we walked all this way for nothing?”, not realising the irony of their pursuit); a woman eyeing me suspiciously, and me her (a lone young man? In those shoes? could have been one of many things crossing her mind).

Up a cut by some houses to Evenley. I’ve no recollection of the village. It’s archetypal, yet unfamiliar: a large green with cricket played out; a village shop on one edge, the Red Lion on another. I feel uneasy that something so quaint and perfect, and so close to where I went to secondary school, can be so alien.

A pint of Oxford Gold: it’s nice to get a local beer, and makes a welcome change to have a smooth, mild pint, instead of the hoppy, citrus-infused punch of so many Scottish craft beers. It’s only mid-afternoon, so I set into another, and read Scarp in the beer garden. Labourers jab friendly insults between each other.

It’s time to leave. The warm spring sun, the alcohol, and the miles of walking conspire to leave me feeling drowsy. Not being fond of retracing my steps, I head out along the western road from the village, to patiently cross the burrel and burl of the A43 dual carriageway. The road I follow is straight: could this be an old Roman road? I don’t enjoy walking along here, as occasional cars speed from behind, forcing me to jump into the verge. But soon I come across the gap in the hedge that signifies the start of the path I have chosen to follow. I say ‘gap’, but it’s more of a thinning: spindly hawthorn attempting to reach through the opening, as though to say: “use it, or we take it back”.

* * *

I have become accustomed to follow helpful waymarkers so far, but this path offers no such luxury. My map doesn’t seem to match the terrain I see ahead, so I make my own way. Behind a farm, with wrecked cars in the field, I wonder: “will the landowner be angry at my prescence? Will he or she see my wandering as an act of wilful trespass?” But really, the fuzz of the beer is numbing these concerns. I get a wave of excitement at this tiny deed of impromptu wayfinding, and think momentarily about Kinder Scout, and how I am walking in the metophorical footsteps of those pioneers. But soon I am away from buildings and potential eyes, and such wistful notions vanish.

Brackley can be spotted again now, on its eversoslightly elevated aspect. My brother links the ‘ley’ suffix to ley lines, while Tom Chivers in his Antidote to Indifference/Island Review essay points out that ‘ey’ is a suffix used for islands, particularly is Sussex. Both fanciful notions, in relation to Brackley, but it brings a smile nonetheless.

Another former road-cum-path and to Saint James’s Lake. I have been walking for hours and my first step back into Brackley is named in honour of St James! I enjoy the aptness of this moment, and read an information board. I am jolted back to the memory of the graffiti earlier: this lake is on the site of two small ponds dug for Brackley Castle (though the lake’s now relatively large size is to attenuate flooding at a nearby housing development).

So Where Brackley Castle? Near here! The castle is no more, this much I know, but as I rise away from lake through 60s and 70s housing, I see a road name: Castle Mount. A small mound, topped with blossoming cherry trees. Could this modest bump be the site of the castle? I see nothing else that lends itself as well this, and besides I’m tired. In my mind, I have found Brackley Castle, and the tagger’s query can be put to rest.